Food safety is all about risk/benefit tradeoffs and trust. I base my consumption choices on lots of factors with risk level, source and production practices amongst them (mixed in with price and taste).

I don’t eat raw sprouts because they’ve been linked to lots of outbreaks; seed stock can be contaminated and there seems to be an inconsistent implementation of best practices. And no one has peeled back the curtain on day-to-day management and marketed food safety by sharing real-time data on irrigation effluent sampling, product sampling or proof of implementation which would increase my trust. The risks don’t outweigh the benefits, to me. The information just isn’t there.

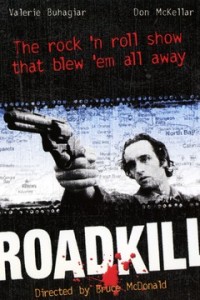

Eating roadkill is another risk/benefit decision. I’ve never had any (that I know of) but it’s not a strictly bad practice/good practice situation. While illegal to harvest side-of-the-road dead animals in some jurisdictions, others, like Montana, are investigating relaxed rules.

The risk/benefit decision is often murky. Food safety is important, but so is actually having food. New friend Andrea Anater of RTI and I shared a guest lecture this week around coping strategies for individuals and families with very low food security and- meaning they often do not have enough to eat and food safety is not as high of a priority as calories. And sometimes people eat roadkill.

Liz Neporant of ABC news reports,

By passing a bill last week that allows motorists to eat their roadkill, the Montana House of Representatives may be on their way to legalizing the ultimate drive-through experience.

State Rep. Steve Lavin originally introduced the bill into Montana’s House to allow “game animals, fur-bearing animals, migratory game birds and upland game birds” who have been killed by a car to be harvested for food.

“This includes deer, elk, moose and antelope, the animals with the most meat,” said Lavin.

“The risk is relative depending on the condition of the animal and how it was killed,” said Benjamin Chapman, a food safety specialist with North Carolina State University. “In roadkill if you happen upon the animal, you don’t know its condition, which makes it riskier than eating regulated food or an animal you’ve hunted.”

Should you decide that flattened moose is what’s for dinner, Chapman advised using a meat thermometer and cooking large game to a temperature of at least 160 degrees Fahrenheit. When dressing the carcass, keep it away from other foods, scrub work surfaces with bleach afterward, and wash hands thoroughly.

Being hungry and sick from foodborne illness (or another zoonoses) isn’t a good thing. The conditions under which the animal died might not be known (like whether it sick when hit) or how long it has been sitting at the side of the road (with pathogens potentially growing and creating toxins). Those are the things I worry about, but I’m fortunate enough to have ready access to food.