I love science.

I also understand its limitations, and the need to continuously question.

I also understand its limitations, and the need to continuously question.

Joanna Klein of the New York Times writes that Dolly the Sheep started her life in a test tube in 1996 – about the same time I got clipped after our fourth daughter was born — and died just six years later.

When Dolly was only a year old, there was evidence that she might have been physically older. At five, she was diagnosed with osteoarthritis. And at six, a CT scan revealed tumors growing in her lungs, likely the result of an incurable infectious disease. Rather than let Dolly suffer, the vets put her to rest.

Poor Dolly never stood a chance. Or did she?

Meet Daisy, Diana, Debbie and Denise. “They’re old ladies. They’re very healthy for their age,” said Kevin Sinclair, a developmental biologist who, with his colleagues at the University of Nottingham in Britain, has answered a longstanding question about whether cloned animals like Dolly age prematurely.

In a study published Tuesday in Nature Communications, the scientists tested these four sheep, created from the same cell line as Dolly, and nine other cloned sheep, finding that, contrary to popular belief, cloned animals appear to age normally.

“They are not monsters,” Pasqualino Loi, a scientist who studies cloning at the University of Terama in Italy and was not involved in the research, wrote in an email.

Dolly’s birth, 20 years ago this month, blew the world away. Scientists had taken a single adult cell from a sheep’s udder, implanted it into an egg cell that had been stripped of its own DNA, and successfully created a living, breathing animal almost genetically identical to its donor.

Sorenne’s birth in 2008 sorta blew me away.

I’d gone through an ugly divorce, went to Kansas, met a girl, and she said she’d like a kid.

I’d gone through an ugly divorce, went to Kansas, met a girl, and she said she’d like a kid.

I told her on the first date I’d had a vasectomy.

But, science can work wonderous things.

And I’m still a kid, in wonder of nature and the science-based explanations.

Any of you getting uncomfortable, this is nothing new, it was all written up in USA Today in 2011 and they took pretty pictures in our house in Kansas which I still use.

So to all those new subscribers to barfblog.com – almost at 70,000 direct – here’s the story.

I’ve found the best therapy for anything is to be public.

Sorenne is developing a sound understanding of genetics. And environment.

The first time William Marsiglio became a dad, he was 18. When his second child was born, he was 49.

The intervening years brought a divorce, a remarriage and a new family.

Marsiglio, a sociologist at the University of Florida-Gainesville, finds himself among an emerging brotherhood of men in their 40s, 50s or 60s rearing young ones again at the same time they have adult children and sometimes grandchildren as well.

This generation of dads — many of them Baby Boomers — married young and had children very young by today’s standards. They did what was expected: worked hard and built careers. Divorce may have followed, then remarriage to a younger partner who wanted kids.

“These men are doing it the second time around, often with women half their age,” says Michael Kimmel, a sociologist at Stony Brook University in Stony Brook, N.Y. He calls the phenomenon “serial paternity.”

The opportunity to have these “sequential families” marks an enormous change for men. Thanks to longer life spans, healthier lifestyles and changing attitudes about divorce and aging, these fathers have a chance, a second chance, to alter their thinking or their actions when it comes to child-rearing. In some cases, they get a do-over.

“There is some sense of wanting to experience a child and a family in a very different way than they did the first time around, and, in their mind, they hope they can get it right this time,” says Marsiglio, 53, who studies fatherhood.

“There is some sense of wanting to experience a child and a family in a very different way than they did the first time around, and, in their mind, they hope they can get it right this time,” says Marsiglio, 53, who studies fatherhood.

“In my case, I hadn’t really embraced feminist principles as I did over time. I’ve changed,” he says. “The financial breadwinner role can be less dominant in their life, and they can look to a more nurturing form of parenting.”

He adds that a new wife or partner may be more career-oriented than the original partner, which requires men to step up to a more co-parenting role.

Experts say it’s not always easy for these dads, who may have thought their child-rearing days were done. Sleepless nights and cranky kids, coupled with pressures from adult children who don’t think their father spends enough time with the grandkids, can create additional family stress, says Kevin Roy, an associate professor of family science who studies fatherhood and trains marriage and family therapists at the University of Maryland-College Park.

But many say it’s worth it.

“What I’m living with now is a blessing,” says Gregg Weinlein, 60, of the Albany, N.Y., suburb of East Greenbush. “I don’t think I do a single thing with my kids that I feel I’m expected to do.”

Weinlein retired last summer after a career as a high school English teacher. His older children, a daughter, Christine, and son, Jesse, are 43 and 37. His younger daughter and son are 11 and 7. He also has two grandsons, ages 8 and 14.

More patience, more time

With his younger kids, Bryel and Beckett, he says he’s the “taxi service” and takes them to activities and is available during the day for school functions. He has breakfast with them and gets them to and from the school bus. It’s a far different story from when his two older kids were young.

“We lived on stereotypes in the late ’60s and early ’70s,” he says. “I really believe that. Women were home and supposed to take care of the kids, and the father was supposed to work.”

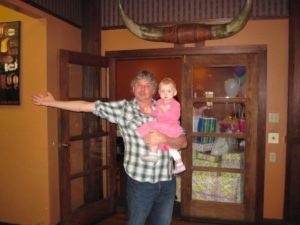

Doug Powell, a professor of food safety at Kansas State University-Manhattan, spends much of his day with his daughter Sorenne, 2.

Because he teaches from home for his distance-learning courses, Powell, 48, has created a routine.

“When she sleeps, I go record lectures on my computer and put on a clean shirt,” he says.

Powell also says he’s a more relaxed parent with his young daughter than he was when his four older daughters were growing up. They range in age from 16 to 24.

“I do enjoy having a 2-year-old to take care of. I just like hanging out with her,” he says.

Powell says he had a vasectomy in 1996, so he and his wife, Amy Hubbell, an associate professor of French at Kansas State, used a sperm donor for Sorenne.

Maurice Colontonio Jr., 60, of Voorhees, N.J., also has five children. He married at age 21 and was married for 18 years until it ended in divorce. His older three children are in their 30s. He remarried at age 40. His young son Joseph was born in 1997, followed by a daughter, Julianna, in 2001.

Maurice Colontonio Jr., 60, of Voorhees, N.J., also has five children. He married at age 21 and was married for 18 years until it ended in divorce. His older three children are in their 30s. He remarried at age 40. His young son Joseph was born in 1997, followed by a daughter, Julianna, in 2001.

Colontonio says he’s more patient as an older father. And because he works less than 20 hours a week as owner and president of a paper recycling company, he can be home to greet the kids when they get off the school bus. His two older sons are vice presidents and run the business, he says.

“I have more time today to spend with the little ones than when I was working 10-15 hour days,” Colontonio says.

Still, “I’ve never felt because he has younger kids that he doesn’t have time for me,” says daughter Jennifer Colontonio, 34, of Phoenixville, Pa. “He definitely makes equal time for all five of us.”

Dads raising kids under 18 do indeed spend more time in child care today than in earlier decades, finds a report released Wednesday by the Pew Research Center, which analyzed data from the 2006-2008 National Survey of Family Growth collected from 13,495 respondents ages 15-44.

In 1965, married fathers with kids under 18 at home spent an average of 2.6 hours a week caring for their children. The amount of time rose to 2.7 hours a week in 1975 and 3 hours a week in 1985. From 1985 to 2000, the amount of time these fathers spent with their children more than doubled, to 6.5 hours a week.

Tom Romero, a Chief Warrant Officer 3 in the U.S. Army, is in Iraq on his third deployment. Romero, 43, has a son Victor, 17, by his first marriage and Joshua, 2, from his current marriage. He has been away from both sons for military service in Iraq.

“I did spend a lot of time away from home that was work-related. I feel bad about that,” Romero says. “I did lose a lot of time with Victor in that respect.”

Keith Strandberg of Pomy, Switzerland says he’s spending about the same amount of time or a little more with his son Jake, 2½, than he did with his two older sons, Calen and Evan, 27 and 25.

But “I find I appreciate the opportunity to spend the time quite a bit more,” he says. “Today, I realize how precious it is to spend time with all the kids.”

Strandberg, who turns 54 in August, is a journalist who covers the watch industry. His first wife, Carol, died in 2005. He married Sophie, now 41, in 2009.

“When my older boys were young, I wasn’t an experienced parent. I may have overreacted to everything,” he says, noting he worries a lot less now.

Health is a concern

But these older dads do worry — about being around to see their kids grow up. As a result, staying active and healthy are among their top priorities.

“I’m kind of a workout monster so I can stay in shape and play with Jake and continue to play with him as he grows older,” Strandberg says.

Colontonio says he has stopped riding motorcyles. He rides a bicycle now instead.

Weinlein, who works out five days a week, says he does think about what he may miss and about his earlier parenting.

“Now, I worry at my age I don’t know the years I have left and what years I’ll miss out as my children get older,” he says. “I wish I had a more mature and accurate vision of life the first time around. It certainly would have helped me as a father.”

Powell says he doesn’t dwell on regrets. “I think we all have regrets, but I’m not sure I would do it any differently. I was 24 when I had my first. Now I’m 48 and I’m a completely different person.”

Having a child with different partners is called multiple-partner fertility and has been studied among low-income men who father children by different women. Social scientists say the research hasn’t kept up with the changes reflected in these sequential families.

Cassandra Dorius of the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor says society needs to adjust its thinking, because this form of multiple-partner fertility is part of a larger trend.

“We’re more open to divorce and remarriage and people don’t have to stay together their whole lives,” Dorius says. “There’s a lot of social acceptance for the idea of moving on.”

When her parents divorced in 1998 after 33 years of marriage, Renee Perelmuter, 41, of Winter Park, Fla., was already married. Her father, who is 64, remarried and has two younger children, ages 7 and 9.

“He’s very hands-on with them,” Perelmuter says. “He probably has more freedom at this point in his life than when I was the age my young siblings are. I don’t feel he loves them any more or any differently. I think the love is all divided equally.

“He really appreciates this second chance at fatherhood very much. He was such a young dad and was working so hard and now he’s able to relax and not sweat the small stuff. He understands what’s more important.”

An Australian woman spent $50,000 on in vitro fertilization, and it didn’t work.

An Australian woman spent $50,000 on in vitro fertilization, and it didn’t work.