Bad things seem to happen around the Victoria Day long weekend in Canada, known up there as May 2-4, because beer is sold in cases of 24 bottles, and Queen Victoria’s birthday was  actually on May 24, 1819, although the long weekend in May to celebrate the start of summer – when youngsters insist on camping and it’s freezing and wet – falls on the Monday either on or before May 24.

actually on May 24, 1819, although the long weekend in May to celebrate the start of summer – when youngsters insist on camping and it’s freezing and wet – falls on the Monday either on or before May 24.

Memorial Day in the U.S. is the last Monday in May.

On May 20, 2003, Canadian officials reported that a single case of BSE was diagnosed in Alberta. The eight-year old cow had been condemned at slaughter, was sent for rendering and did not enter the food chain. Although an isolated case, Canada was no longer free of homegrown Mad Cow Disease.

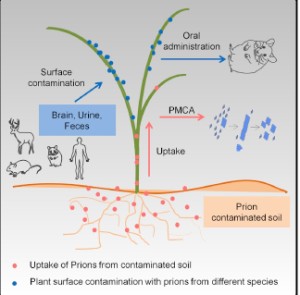

Mad Cow Disease or bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) is a chronic degenerative illness that affects the central nervous system of cattle. It is part of a family of rare diseases whose different forms affect different species of animals.

As the elementary school year wound down in June, 2003, in Ontario, Canada, the school three of my daughters attended had a barbeque for students, staff and parents.

The earlier discovery of BSE in Canada was of concern to some parents and school officials, so a note was sent home to parents, assuring them that the hamburgers and hot dogs to be consumed came from a supplier of so-called natural, beef and was therefore safe from BSE.

Leaving aside the scientific validity of such a statement (it’s not), the concerns about a potentially catastrophic, poorly understood risk, while completely valid, can also mask the concerns, biases and threats presented by less-exotic food-related risks.

At this particular BBQ, several of the well-meaning volunteer cooks were observed to handle the raw, natural hamburger patties with tongs that were then used to place re-heated  wieners into hot dog buns, possibly cross-contaminating the wieners with any number of pathogenic microorganisms such as E. coli O157:H7, salmonella or listeria, and subsequently served to parents and children.

wieners into hot dog buns, possibly cross-contaminating the wieners with any number of pathogenic microorganisms such as E. coli O157:H7, salmonella or listeria, and subsequently served to parents and children.

In terms of food safety, the observed practices represented a far greater risk; sure, mad cow disease, with all its unknowns, is bad, but with all the attention being paid to the hypothetical risks associated with BSE and genetically-engineered foods, many of the consumers whose confidence is vital to the food business are being distracted from the basics.

The efforts exerted by farmers, processors, retailers and consumers to ensure safe food are greater than ever. Yet the public discourse is increasingly focused on hypothetical food-related risks, which makes great barroom chatter, but does little to alleviate the suffering like that experienced by the 56 high school seniors in Ontario stricken around the same time with E. coli O157:H7 and were more rightly more concerned about future plans and making an impression on their date.

Oh, and unlike every other country that has discovered BSE, consumption of beef actually increased. While price discounts, advertising, and promotional statements from various social actors about the safety of Canadian beef probably contributed to the sales increase, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency was completely transparent, publicly showcasing — in the form of daily press conferences lead by Canada’s chief veterinarian, Dr. Brian Evans — a vigilant, proactive regulatory system, while acknowledging the likelihood that the disease was not limited to just one animal. In essence, Dr. Evans and his team provided daily  updates that said, this is what we know, this is what we don’t know, and this is what we’re doing to find out more. And when we find out more, you will hear it from us first. Transparency, along with efforts to demonstrable that actions match words, is the best way to enhance consumer confidence.

updates that said, this is what we know, this is what we don’t know, and this is what we’re doing to find out more. And when we find out more, you will hear it from us first. Transparency, along with efforts to demonstrable that actions match words, is the best way to enhance consumer confidence.

May 20, 2003, was also the day Justin Kastner successfully defended his PhD under my supervision at the University of Guelph. Kastner got on faculty at Kansas State, arranged for me to visit in fall 2005, I met a girl, got a job offer, and am still in Kansas. That wasn’t a bad thing. I will write about other bad Victoria Day stuff tomorrow.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency released a report Monday that says no part of the Black Angus beef cow entered the human food or animal feed systems.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency released a report Monday that says no part of the Black Angus beef cow entered the human food or animal feed systems.

actually on May 24, 1819, although the long weekend in May to celebrate the start of summer – when youngsters insist on camping and it’s freezing and wet – falls on the Monday either on or before May 24.

actually on May 24, 1819, although the long weekend in May to celebrate the start of summer – when youngsters insist on camping and it’s freezing and wet – falls on the Monday either on or before May 24.