In honor of Chuck Dodd successfully defending his PhD yesterday at Kansas State University, I decided to crack open the military Meal Ready to Eat (MRE) he’d given to me a couple of years ago.

In June 2008, The Christian Science Monitor reported about Jeanette Kennedy, a food technologist at the US Army Natick Soldier Systems Center (NSSC) west of Boston. Kennedy faces creative challenges unlike those  before any other chef because she creates MREs, designed to fuel soldiers lugging 100-pound packs all day.

before any other chef because she creates MREs, designed to fuel soldiers lugging 100-pound packs all day.

The story says that meals can’t just taste good; they’ve got to last … for three years stored at 80 degrees F., be capable of withstanding chemical or biological attacks, and survive a 10-story free fall (when packed in a crate of 12).

MREs were first served in the 1980s when canned fare gave way to meals packed in sturdy beige pouches. Others have called them Meals Rejected by the Enemy, Meals Rarely Edible, and Meals Refusing to Exit (a name that continues to stick despite the addition of more fiber).

Troop acceptance of the meals, which cost the military $7.13 each, has taken center stage. Back in 1982 when MREs debuted, designers assumed they could hang up their aprons. But when the first Gulf War broke out, the new ration moved from limited training use to the only food soldiers ate for months on end. Angry letters flooded in from the trenches, and the military realized that rations had to be a work in progress.

Now food technologists conduct focus groups with troops across the country, follow restaurant fads, and even attend culinary school to make sure  their approach isn’t entirely scientific.

their approach isn’t entirely scientific.

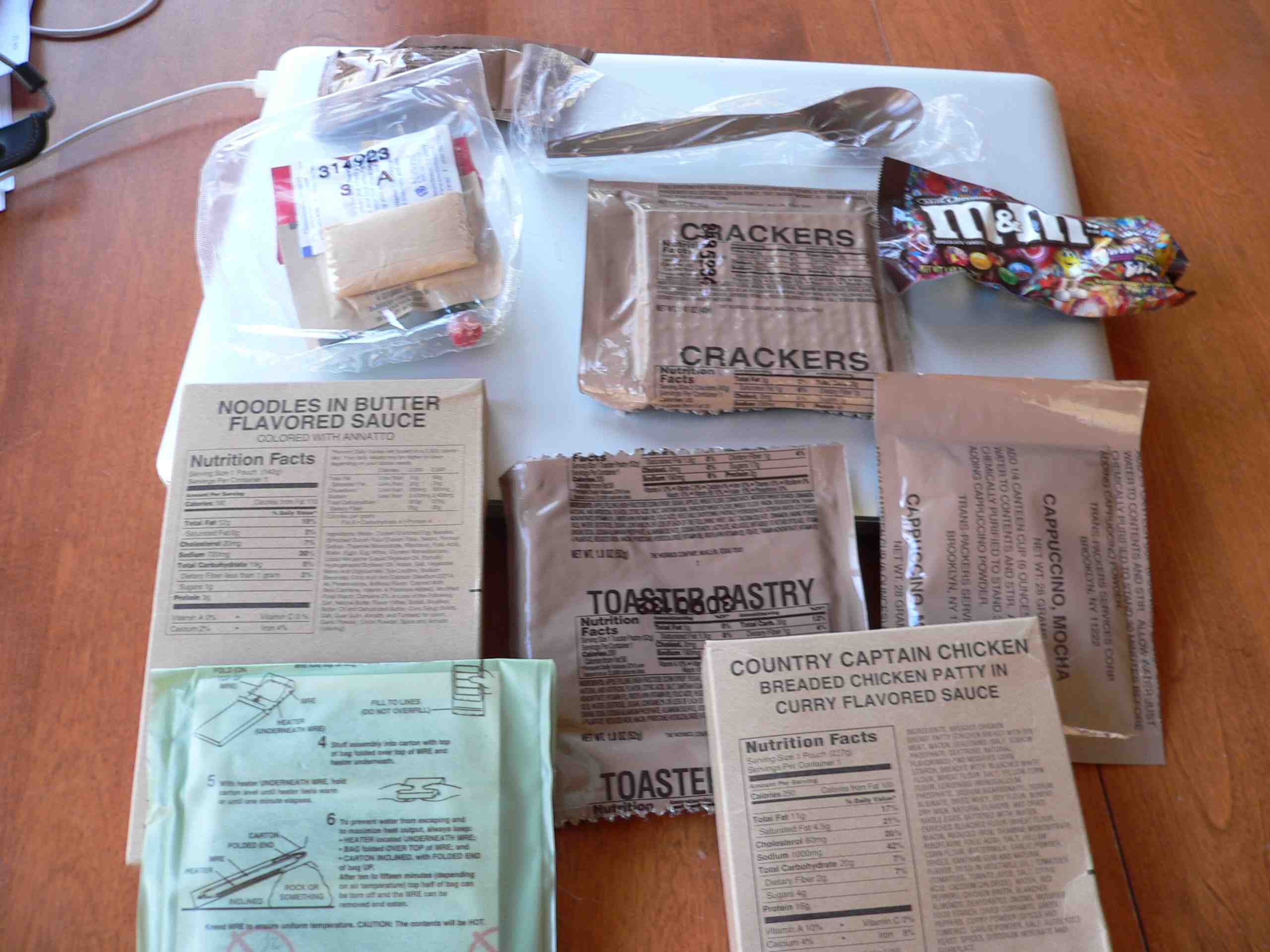

The MRE I had contained noodles in butter-flavored sauce, cheese spread, breaded chicken patty in curry-flavored sauce, toaster pastry, crackers, cappuccino, condiments, and of course, M&Ms. The activated heater pouch to warm food and coffee MREs was particularly innovative. The food? I wouldn’t want to live on it.

In 2008, chef Kennedy said, "[MREs] really go along with the trends. As new things come out at restaurants, new flavors like chipotle or buffalo [get popular], they get incorporated into the MRE…. The trend [now is] going to more comfort foods like Salisbury steak, beef briquette, but it’s not just macaroni and cheese, it’s Mexican macaroni and cheese."

The

The