Amy’s father and stepmom came for a visit and yesterday we went to a local eatery for a late lunch.

When Amy’s dad ordered a burger, the server asked how he would like the burger cooked.

He said medium-well.

He said medium-well.

The server said he could get the burger as rare as he wanted.

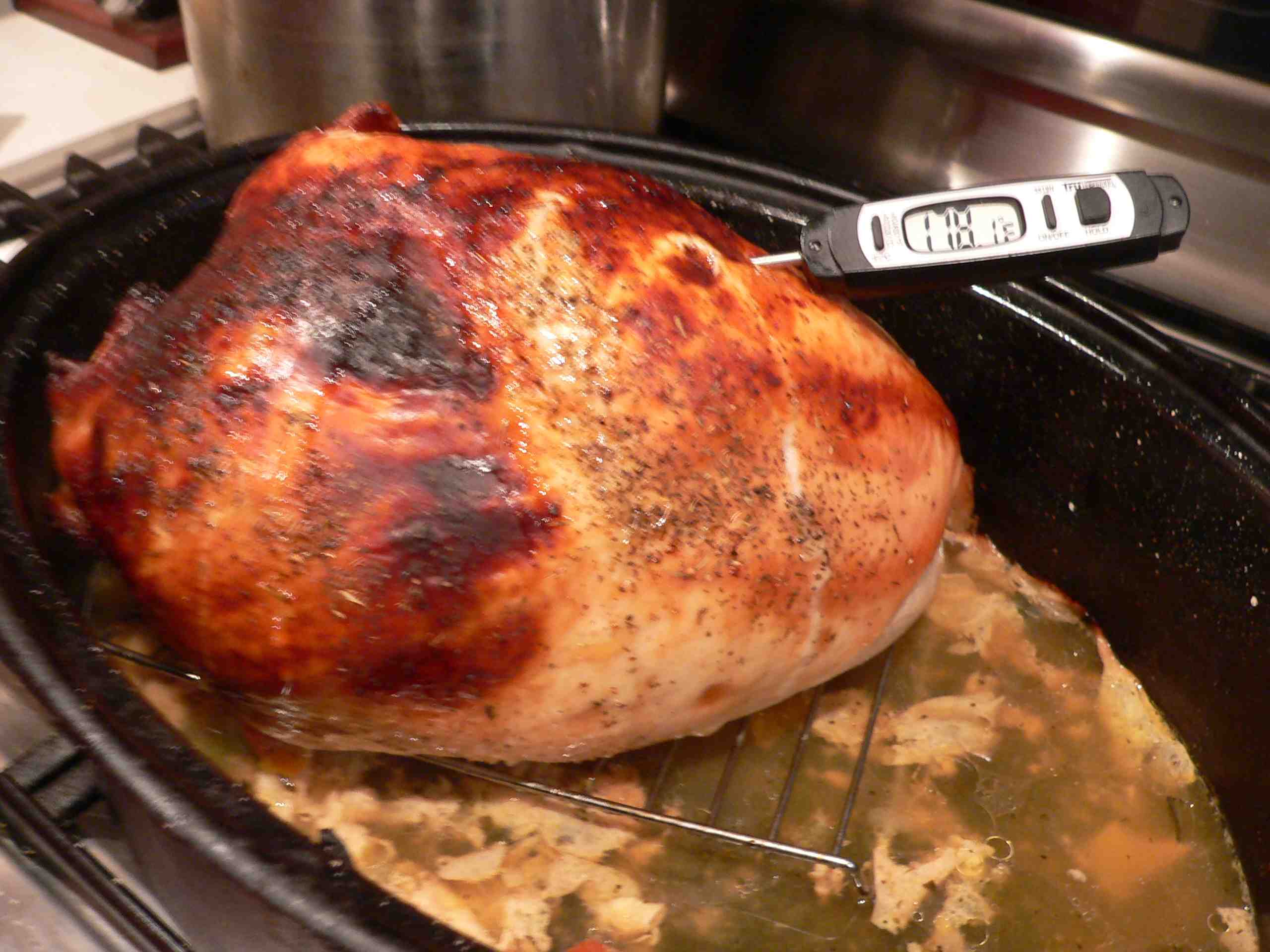

Amy said really, and started asking, just what was a medium-rare burger.

The server said it all had to do with color, and after some back and forth with the cooks, said the beef they get has nothing bad in it anyway.

Color is a lousy indicator.

During the same meal, a reporter called to ask, why do companies – big companies, huge chains and brand names — knowingly follow or ignore bad safety practices? (that story should appear Sunday).

It comes down to culture – the food safety culture of a restaurant, a supermarket, a butcher shop, a government agency.

Culture encompasses the shared values, mores, customary practices, inherited traditions, and prevailing habits of communities. The culture of today’s food system (including its farms, food processing facilities, domestic and international distribution channels, retail outlets, restaurants, and domestic kitchens) is saturated with information but short on behavioral-change insights. Creating a culture of food safety requires application of the best science with the best management and communication systems, including compelling, rapid, relevant, reliable and repeated, multi-linguistic and culturally-sensitive messages.

Sixteen years after E. coli O157:H7 killed four and sickened hundreds who ate hamburgers at the Jack-in-the-Box chain, the challenge remains: how to get people to take food safety seriously? ??????Lots of companies do take food safety seriously and the bulk of American meals are microbiologically safe. But recent food safety failures have been so extravagant, so insidious and so continual that consumers must feel betrayed.??????

Frank Yiannas, the vice-president of food safety at Wal-Mart writes in his book, Food Safety Culture: Creating a Behavior-based Food Safety Management System, that an organization’s food safety systems need to be an integral part of its culture.

The other guru of food safety culture, Chris Griffith of the University of Wales, features prominently in the report by Professor Hugh Pennington into the 2005 E.coli outbreak in Wales that killed 5-year-old Mason Jones and sickened another 160 school kids.

Yesterday, the board of the U.K. Food Standards Agency (FSA), in response to Pennington’s report, approved a five-year plan that will push food businesses to adopt a food safety culture and comply with hygiene laws, and urge stricter punishments for those that do not. The FSA will also ensure health inspectors are better trained.

Yesterday, the board of the U.K. Food Standards Agency (FSA), in response to Pennington’s report, approved a five-year plan that will push food businesses to adopt a food safety culture and comply with hygiene laws, and urge stricter punishments for those that do not. The FSA will also ensure health inspectors are better trained.

A report put before FSA board members in London stated “culture change in all of the relevant parts of the food supply chain” is necessary.

Mason Jones’ mum Sharon Mills said she is pleased with the action being taken by the FSA.

“This sounds promising and shows they are moving in the right direction. … Things are slowly changing and hopefully we will all see the benefits sooner rather than later.”

Maybe. I’m still not convinced FSA understands what culture is all about. And how will these changes be evaluated. Is there any evidence that social marketing is effective in creating food safety behavior change? Those issues get to the essence of food safety culture, yet are glossed over with a training session – more of the same.

And why wait for government. The best food producers, processors, retailers and restaurants should go above and beyond minimal government and auditor standards and sell food safety solutions directly to the public. The best organizations will use their own people to demand ingredients from the best suppliers; use a mixture of encouragement and enforcement to foster a food safety culture; and use technology to be transparent — whether it’s live webcams in the facility or real-time test results on the website — to help restore the shattered trust with the buying public.

.jpeg)

The Food Standards Agency today published the findings of a new survey testing for campylobacter and salmonella in chicken on sale in the U.K.

The Food Standards Agency today published the findings of a new survey testing for campylobacter and salmonella in chicken on sale in the U.K.(2).jpg)

.jpg) So she did.

So she did.  He said medium-well.

He said medium-well. Y

Y.jpeg)

.jpg) Today, the

Today, the Ling Zhang and her company Ling Ling Poultry pleaded guilty in Papakura District Court last week to four charges under the Animal Products Act.

Ling Zhang and her company Ling Ling Poultry pleaded guilty in Papakura District Court last week to four charges under the Animal Products Act. The court heard that on 25 December 2006, Pierson’s restaurant provided a Christmas Day buffet luncheon for about 110 diners, with a selection of ham, beef and turkey. The next day some of the diners called him complaining of illness after the luncheon. Fifty-seven reported varying degrees of stomach pain, abdominal cramps and diarrhoea.

The court heard that on 25 December 2006, Pierson’s restaurant provided a Christmas Day buffet luncheon for about 110 diners, with a selection of ham, beef and turkey. The next day some of the diners called him complaining of illness after the luncheon. Fifty-seven reported varying degrees of stomach pain, abdominal cramps and diarrhoea..jpg) The take home messages: build trust, get out of the office, and be in it for the long term. That’s Philippa (right), with Curtis Kastner, director of Kansas State’s Food Science Institute, me, Philippa, and Lisa Freeman, associate dean for research at K-State’s vet college, and a v.p. at K-State’s new Olathe innovation campus.

The take home messages: build trust, get out of the office, and be in it for the long term. That’s Philippa (right), with Curtis Kastner, director of Kansas State’s Food Science Institute, me, Philippa, and Lisa Freeman, associate dean for research at K-State’s vet college, and a v.p. at K-State’s new Olathe innovation campus..jpg) The waiter didn’t have a clue, but did offer to ask, returned from the kitchen, and said it was made from pasteurized milk, and someone had asked the chef the same question last week.

The waiter didn’t have a clue, but did offer to ask, returned from the kitchen, and said it was made from pasteurized milk, and someone had asked the chef the same question last week. Wellington, New Zealand, may be home to Peter Jackson and the Ring things, may be where Bret and Jemaine from

Wellington, New Zealand, may be home to Peter Jackson and the Ring things, may be where Bret and Jemaine from

Saturday evening, NZFSA chief executive Andrew McKenzie (right) and his wife shared their home and their spectacular view of Wellington for dinner and an evening of All Blacks rugby against South Africa.

Saturday evening, NZFSA chief executive Andrew McKenzie (right) and his wife shared their home and their spectacular view of Wellington for dinner and an evening of All Blacks rugby against South Africa. The coffee place was just opening and as I awaited my order, a load of prepared sandwiches arrived. The first thing the staff member did was insert a tip-sensitive digital thermometer into one of the sandwiches to verify that the proper temperature had been maintained. Good on ya. The guy getting my order said it was standard operating procedure, and as we chatted it emerged he was newly arrived in Wellington from Montreal. Another Canadian buddy. Or friend.

The coffee place was just opening and as I awaited my order, a load of prepared sandwiches arrived. The first thing the staff member did was insert a tip-sensitive digital thermometer into one of the sandwiches to verify that the proper temperature had been maintained. Good on ya. The guy getting my order said it was standard operating procedure, and as we chatted it emerged he was newly arrived in Wellington from Montreal. Another Canadian buddy. Or friend. Being in Wellington, NZ, and 17 hours ahead, provided several technological hurdles, which we sorta managed to get around. Video didn’t work, so the folks in Nebraska saw

Being in Wellington, NZ, and 17 hours ahead, provided several technological hurdles, which we sorta managed to get around. Video didn’t work, so the folks in Nebraska saw .jpg)