Persons in congregate work and residential locations are at increased risk for transmission and acquisition of respiratory infections.

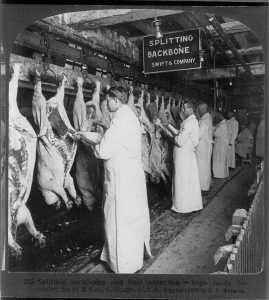

COVID-19 cases among U.S. workers in 115 meat and poultry processing facilities were reported by 19 states. Among approximately 130,000 workers at these facilities, 4,913 cases and 20 deaths occurred. Factors potentially affecting risk for infection include difficulties with workplace physical distancing and hygiene and crowded living and transportation conditions.

COVID-19 cases among U.S. workers in 115 meat and poultry processing facilities were reported by 19 states. Among approximately 130,000 workers at these facilities, 4,913 cases and 20 deaths occurred. Factors potentially affecting risk for infection include difficulties with workplace physical distancing and hygiene and crowded living and transportation conditions.

Improving physical distancing, hand hygiene, cleaning and disinfection, and medical leave policies, and providing educational materials in languages spoken by workers might help reduce COVID-19 in these settings and help preserve the function of this critical infrastructure industry.

COVID-19 among workers in meat and poultry processing facilities—19 States, April 2020, 08 May 2020

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report pp. 557-561d

Jonathan W. Dyal, MD1,2; Michael P. Grant, ScD1; Kendra Broadwater, MPH1; Adam Bjork, PhD1; Michelle A. Waltenburg, DVM1,2; John D. Gibbins, DVM1; Christa Hale, DVM1; Maggie Silver, MPH1; Marc Fischer, MD1; Jonathan Steinberg, MPH1,2,3; Colin A. Basler, DVM1; Jesica R. Jacobs, PhD1,4; Erin D. Kennedy, DVM1; Suzanne Tomasi, DVM1; Douglas Trout, MD1; Jennifer Hornsby-Myers, MS1; Nadia L. Oussayef, JD1; Lisa J. Delaney, MS1; Ketki Patel, MD, PhD5; Varun Shetty, MD1,2,5; Kelly E. Kline, MPH6; Betsy Schroeder, DVM6; Rachel K. Herlihy, MD7; Jennifer House, DVM7; Rachel Jervis, MPH7; Joshua L. Clayton, PhD3; Dustin Ortbahn, MPH3; Connie Austin, DVM, PhD8; Erica Berl, DVM9; Zack Moore, MD9; Bryan F. Buss, DVM10,11; Derry Stover, MPH10; Ryan Westergaard, MD, PhD12; Ian Pray, PhD2,12; Meghan DeBolt, MPH13; Amy Person, MD14; Julie Gabel, DVM15; Theresa S. Kittle, MPH16; Pamela Hendren17; Charles Rhea, MPH17; Caroline Holsinger, DrPH18; John Dunn19; George Turabelidze20; Farah S. Ahmed, PhD21; Siestke deFijter, MS22; Caitlin S. Pedati, MD23; Karyl Rattay, MD24; Erica E. Smith, PhD24; Carolina Luna-Pinto, MPH1; Laura A. Cooley, MD1; Sharon Saydah, PhD1; Nykiconia D. Preacely, DrPH1; Ryan A. Maddox, PhD1; Elizabeth Lundeen, PhD1; Bradley Goodwin, PhD1; Sandor E. Karpathy, PhD1; Sean Griffing, PhD1; Mary M. Jenkins, PhD1; Garry Lowry, MPH1; Rachel D. Schwarz, MPH1; Jonathan Yoder, MPH1; Georgina Peacock, MD1; Henry T. Walke, MD1; Dale A. Rose, PhD1; Margaret A. Honein, PhD

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6918e3.htm?s_cid=mm6918e3_e&deliveryName=USCDC_921-DM27591

infection came from this abattoir. The management of the slaughterhouse confirmed on their part that it is not out of the question that the victims kept the filet américain (that made them sick) in a place that was not sufficiently cold. But it also admits that the infection could have come from within the slaughterhouse, in spite of strict hygiene tests.

infection came from this abattoir. The management of the slaughterhouse confirmed on their part that it is not out of the question that the victims kept the filet américain (that made them sick) in a place that was not sufficiently cold. But it also admits that the infection could have come from within the slaughterhouse, in spite of strict hygiene tests. research evaluating measures on farms and in slaughterhouses to reduce levels of dangerous E. coli.

research evaluating measures on farms and in slaughterhouses to reduce levels of dangerous E. coli..jpg) water in the shower was of a good microbiological, chemical and physical quality. Immediately after pasteurization, the meat was rather pale, but it regained its normal colour after being cooled for 24 hours.

water in the shower was of a good microbiological, chemical and physical quality. Immediately after pasteurization, the meat was rather pale, but it regained its normal colour after being cooled for 24 hours.