| “President Myers and Provost Taber are leading K-State forward in unprecedented ways. I love being part of their team and working with faculty and staff, my fellow deans and other university administrators. However, it is imperative to focus on succession planning, especially with the new budget model and strategic enrollment management initiatives coming on board. I want the new leader of the Olathe campus to be well prepared to embrace the opportunities that are coming to K-State through engagement with Greater Kansas City.”

Under Dr. Richardson’s leadership, K-State used the Olathe campus to expand its outreach and services to Greater Kansas City to elevate the university’s profile in academics, research and service in the region and generate new opportunities for students and faculty.

Dr. Richardson helped establish and oversee numerous partnerships that are being used to develop a recruitment and support infrastructure for Kansas City-based undergraduate students to attend K-State and working professionals to enroll at the university’s Olathe campus.

Before his appointment overseeing the Olathe campus, Dr. Richardson served as dean of the university’s College of Veterinary Medicine for 17 years. Under his guidance, the college experienced increased student enrollment; raised more than $72 million in private support for scholarships and seven permanently endowed professorships; introduced the Veterinary Training Program for Rural Kansas, which offers a debt repayment incentive for graduates to work in rural practices in Kansas; increased faculty and staff numbers, with many receiving national and international attention for their teaching, research and service efforts; aligned research and educational programs to meet the needs of the federal government’s National Bio and Agro-defense Facility, or NBAF, which is being built just north of the college; and much more.

Dr. Richardson joined Kansas State University in 1998, coming from Purdue University where he was a professor and head of the veterinary clinical sciences department and a 22-year faculty member of the university. At Purdue, he helped establish an ongoing comparative oncology program, utilizing naturally occurring cancer in pet animals as models for people. Before starting his academic career, Richardson served in the Army Veterinary Corps and worked as a private practice veterinarian in Miami.

Back to the story. Back to the story.

Ralph knew me because when he was at Purdue, he signed up to AnimalNet, one of those listserves that is now obsolete but was radical at the time.

When I met him in person, he was like an old friend, because if you get an e-mail from someone every day, they are like old friends.

After another week I went back to Canada, spoke with my four daughters, and decided, I should be in Kansas. Curt Kastner (the only uninvited dude who showed up at our city hall wedding, because we didn’t invite anyone except the witnesses, much thanks Pete and Angelique) called and said, can I arrange a conference call with Ralph?

I said, why don’t I show up in person?

Next day I was on a flight. I did a TV interview at the Toronto airport as I was departing, about a raw sprouts outbreak that had sickened at least 400 in Ontario (that’s a province in Canada), and within 24 hours, I was in Ralph’s living room, because he had broken his ankle or something while hunting, and was propped up on the couch.

I told him my vision of food safety risk analysis and research and outreach, and he told me he’d see what he could do.

I went and hung out with the girl.

In December, I decided to take the girl to Canada to see if my friends approved, because my solo judgement in such areas had proven awful.

They approved.

On my birthday, Dec. 29, 2005, me and the girl were in a grocery store in Guelph, and Ralph called. He said, we’d like to make you a job offer, how’s $100,000 U.S., plus lab start-up fees?

I was ecstatic.

Within months, me and the girl had bought our own house in Manhattan, Kansas, I was brimming with ideas, the E. coli O157:H7 outbreak in spinach started in Sept. 2006 and I was splashed all over American media as someone who may know something about this stuff. Kansas State benefited, and the president would call me weekly and say, great job.

However, back in the veterinary college, the other faculty didn’t really know what to make of me: except Dean Ralph.

I got made a full professor in 2010, but the increasing bureaucracy was not to my liking.

I loved the other aspects of my job, and I loved my wife and family.

So when Dr. Amy Hubbell, formerly of Kansas State University, was offered a faculty appointment at the University of Queensland, I wasn’t gonna be the guy who said no.

It would have been real easy to stay in Kansas, but that wasn’t our style.

So Amy and Sorenne went off to Australia, and I eventually caught up.

I worked by distance at Kansas State. I worked by distance at Kansas State.

But other profs started nitpicking.

Our first guest on the first day we moved into the first place we owned rather than rented in 2012 was Dr. Clorox (that’s what they called him in Korea).

Kansas State knew we were in Brisbane, I was still an employee of K-State, but no one bothered to reach out as K-State tried to set up a partnership with the University of Queensland.

I told Ralph that evening, no hard feelings if you have to get rid of me, universities can be small sandboxes with too many and too big egos.

I had presented options for on-line course in food safety policy, a massive open on-line course (MOOC) in food safety, take a 20 per cent pay cut and was repeatedly told my performance as a faculty member was above average – but I got fired for not being there to hold my colleagues hand during tea.

The bosses at Kansas State University determined I had to be on campus, I said no, so I was dumped.

Full professors can get dumped for bad attendance.

I love my wife and family. And that’s where my allegiance lies.

It’s been harder than I thought it would be, I’ve unfortunately expressed my rage to my wife at silly times in silly ways, my brain is degenerating for a variety of reasons, but I’m optimistic, and in addition to the Kastners, Dr. Clorox has been a big fan and a good friend.

Ralph, thanks for all you’ve done for Amy and I, enjoy that retirement, and try not to drive Bev crazy hanging around the house. |

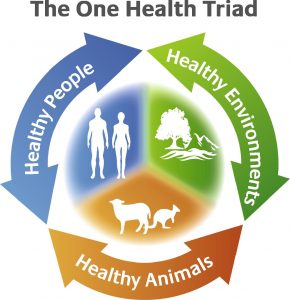

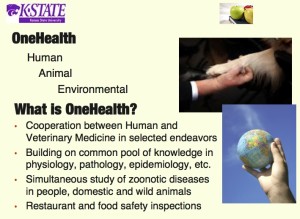

The American Medical Association and the American Veterinary Medical Association have approved resolutions supporting ‘One Medicine’ or ‘One Health’ that bridge the two professions. Rudolf Virchow, the Father of Modern Pathology, and Sir William Osler, the Father of Modern Medicine, were outspoken advocates of the concept, which was re-articulated in the 1984 edition of Calvin Schwabe’s Veterinary Medicine and Human Health.

The American Medical Association and the American Veterinary Medical Association have approved resolutions supporting ‘One Medicine’ or ‘One Health’ that bridge the two professions. Rudolf Virchow, the Father of Modern Pathology, and Sir William Osler, the Father of Modern Medicine, were outspoken advocates of the concept, which was re-articulated in the 1984 edition of Calvin Schwabe’s Veterinary Medicine and Human Health. Drawing on the agency’s experience in past animal health emergencies, the One Health initiative aims to make a key contribution to the global response to disease outbreaks, implementation of effective prevention and containment strategies and management of risks of disease emergence, including improving knowledge of disease-emergence drivers in livestock production and in associated ecosystems.

Drawing on the agency’s experience in past animal health emergencies, the One Health initiative aims to make a key contribution to the global response to disease outbreaks, implementation of effective prevention and containment strategies and management of risks of disease emergence, including improving knowledge of disease-emergence drivers in livestock production and in associated ecosystems.