Stacy Stevens, who leads the Issues & Crisis Navigation practice at FoodMinds LLC in Chicago writes in O’Dwyer’s Communications & New Media that microbiological pathogens lurk around every drain, every ceiling tile that collects condensation and every box of ingredients unpacked in a restaurant kitchen.

Food and beverage companies are speaking out about the healthfulness and wholesomeness of their products, as well as the integrity of their supply chains and their commitments to farm animal care and environmental sustainability, to maintain consumer confidence and trust. That carefully-constructed bond with consumers can dissipate in an instant with the emergence of a food safety concern. Here’s how communication pros can work in lock-step with their operations counterparts to prevent a food safety compromise and keep their hard-earned reputations intact.

Food and beverage companies are speaking out about the healthfulness and wholesomeness of their products, as well as the integrity of their supply chains and their commitments to farm animal care and environmental sustainability, to maintain consumer confidence and trust. That carefully-constructed bond with consumers can dissipate in an instant with the emergence of a food safety concern. Here’s how communication pros can work in lock-step with their operations counterparts to prevent a food safety compromise and keep their hard-earned reputations intact.

Most of us practitioners of public relations don’t claim to understand the finer distinctions between Listeria monocytogenes, Clostridium botulinum and Escherichia coli. So, how can we ensure our companies and clients stay out of the “tag, CDC says you’re it” spotlight?

Dairy Forum 2016, a gathering of 1,100 food industry executives from around the globe hosted by International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA) in late January, explored this question in the session “Caution: Company Under Pressure,” which I had the honor of moderating.

According to panel member Joe Levitt, partner at Hogan Lovells and former director of FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, the single biggest problem is thinking this can’t or won’t happen to you.

Communicators: it’s our job to get our companies and clients past that mindset, and once we do, the path to preparedness — and ideally prevention — is clear:

Your QA team is reexamining and reinventing its system from top to bottom.

There’s no such thing as zero risk. And pledging to adopt the very highest food safety standards represents a major investment of time and resources. At The Ice Cream Club, headquartered in Boynton Beach, Fla., company owners watched the Listeria outbreaks linked to ice cream in 2015 with trepidation. But they didn’t just watch, they sprang into action. They brought in outside auditors, instructing them, “We’re not looking for a gold star; we want you to thoroughly review our facility for any areas of risk and opportunities to improve!” They installed new equipment, joined IDFA’s Listeria Task Force, updated protocols and methodically retrained their employees. Importantly, they walked the production facility floor day-in-and-day-out, visibly modeling the behaviors they wanted employees to follow. This was a critical success factor in helping employees acclimate to the dynamic new food safety culture.

There’s no such thing as zero risk. And pledging to adopt the very highest food safety standards represents a major investment of time and resources. At The Ice Cream Club, headquartered in Boynton Beach, Fla., company owners watched the Listeria outbreaks linked to ice cream in 2015 with trepidation. But they didn’t just watch, they sprang into action. They brought in outside auditors, instructing them, “We’re not looking for a gold star; we want you to thoroughly review our facility for any areas of risk and opportunities to improve!” They installed new equipment, joined IDFA’s Listeria Task Force, updated protocols and methodically retrained their employees. Importantly, they walked the production facility floor day-in-and-day-out, visibly modeling the behaviors they wanted employees to follow. This was a critical success factor in helping employees acclimate to the dynamic new food safety culture.

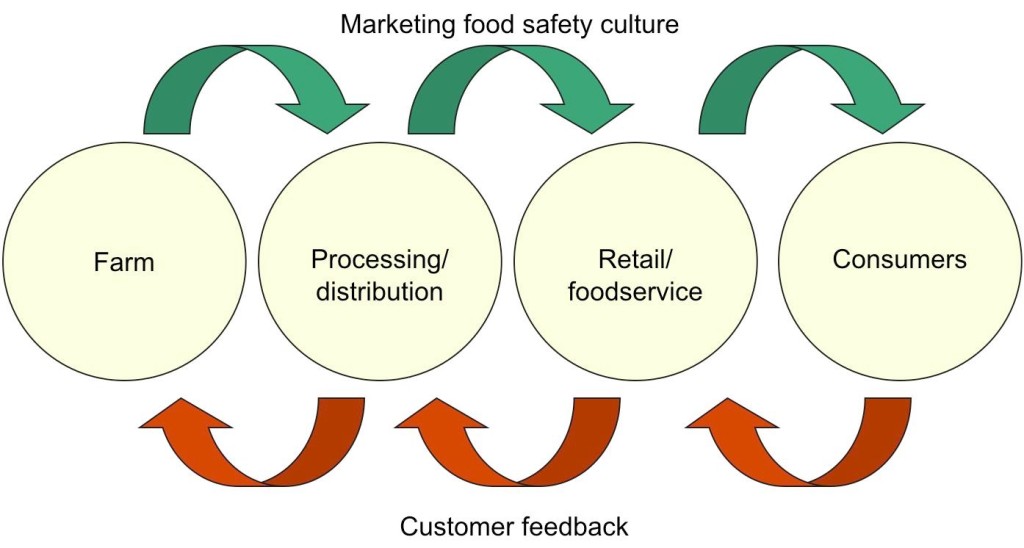

Communicators have pressing media interviews to conduct, content strategies to approve and executives to prep for the next earnings call. But the historic legislation that directed FDA to build a new system of food safety oversight – one focused on applying the best available science along with common sense, to prevent outbreaks of foodborne illness, must be part of our jobs too. Make sure you understand what your operations team is doing in light of the multi-year implementation of Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) regulations, and update your food safety and quality messaging and proof points accordingly. Then, take it upon yourself to make sure your quality assurance, supply chain management and science/regulatory experts appreciate the importance of reputation management, issues management and crisis communication to their efforts. And make sure your FSMA-compliant Recall Plan includes the communications plan and assets you’ll need to deploy in order to properly notify customers and the public when necessary.

The key to the success of any response-mode communication effort is that your stakeholders and the general public already know your name and enough about you to give you the benefit of the doubt when something negative surfaces. The best way for members of the food industry to ensure this is the case, is to visibly engage in corporate social responsibility, responsible sourcing, nutrition, health & wellness and sustainability efforts. Make meaningful commitments and talk to the public – online and offline – about them in an authentic and passionate way.

The key to the success of any response-mode communication effort is that your stakeholders and the general public already know your name and enough about you to give you the benefit of the doubt when something negative surfaces. The best way for members of the food industry to ensure this is the case, is to visibly engage in corporate social responsibility, responsible sourcing, nutrition, health & wellness and sustainability efforts. Make meaningful commitments and talk to the public – online and offline – about them in an authentic and passionate way.

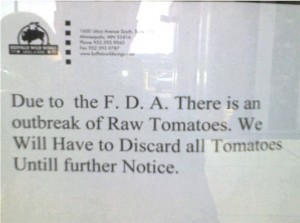

Your crisis plan should be a living, breathing arsenal of strategies, checklists and tactics so you and your colleagues can respond without losing time to internal deliberations (“is this a four-alarm fire, or a three-alarm fire?”) when something hits. You’re going to need to marshal external resources quickly as well, so your plan should map out your network of legal, scientific, communications and operational advisors. And remember that scenario-based tabletop exercise that got cut from last year’s budget? It certainly would have been helpful if the key players had gotten a practice session in before the playbook was put to use!

Your third-party academic experts know you, and can speak to your track record.

The list of third-party experts compiled by your summer intern isn’t going to do much good in a crisis if you haven’t built and maintained relationships with everyone on it. Invite scientific and academic experts to tour your facilities, make an effort to visit their institutions, and update them regularly on company events and milestones.

When your brand or company reputation is called into question, you’re not alone. Industry associations such as IDFA have communication resources — social media monitoring dashboards, for example, and they employ technical experts who maintain strong relationships with federal regulators. They can advise you on preventive controls and communication strategies to shore up your prevention plan and are well equipped to buoy your team in the event of an escalated issue or crisis.

The stakes for food and beverage executives are higher than ever as FDA becomes increasingly aggressive in using the criminal sections of the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) in the wake of food safety incidents. There have been more criminal prosecutions in the past five years of food company managers than in the prior two decades combined. And it’s important to realize that a misdemeanor conviction under the FDCA does not require proof of fraudulent intent, and doesn’t even require that managers were aware of a potential safety issue.

With a culture of food safety excellence and crisis preparedness in place, you may not avoid “tag, you’re it” entirely but you’ll be in a much better position to get back-into-the-game, and back-to-business, as quickly as possible.

professional aboard the flight?”

professional aboard the flight?” Journey is so awful – over the years.

Journey is so awful – over the years. never enough when faced with a risky situation – it’s the combination of risk assessment and management, along with communications, that helps individuals, corporations and governments regain trust and public favor.

never enough when faced with a risky situation – it’s the combination of risk assessment and management, along with communications, that helps individuals, corporations and governments regain trust and public favor. In 1999, the Belgian government delayed communicating with the public and other European agencies about possible risks, failed to acknowledge perceived risks with dioxin-laden feed, and ultimately suffered huge economic losses, a damaged food industry and deterioration in public confidence.

In 1999, the Belgian government delayed communicating with the public and other European agencies about possible risks, failed to acknowledge perceived risks with dioxin-laden feed, and ultimately suffered huge economic losses, a damaged food industry and deterioration in public confidence.