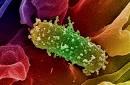

UT Southwestern Medical Center microbiologists have identified key bacteria in the gut whose resources are hijacked to spread harmful foodborne E. coli infections and other intestinal illnesses.

Though many E. coli bacteria are harmless and critical to gut health, some E. coli species are harmful and can be spread through contaminated food and water, causing diarrhea and other intestinal illnesses. Among them is enterohemorrhagic E. coli or EHEC, one of the most common foodborne pathogens linked with outbreaks featured in the news, including the multistate outbreaks tied to raw sprouts and ground beef in 2014.

Though many E. coli bacteria are harmless and critical to gut health, some E. coli species are harmful and can be spread through contaminated food and water, causing diarrhea and other intestinal illnesses. Among them is enterohemorrhagic E. coli or EHEC, one of the most common foodborne pathogens linked with outbreaks featured in the news, including the multistate outbreaks tied to raw sprouts and ground beef in 2014.

The UT Southwestern team discovered that EHEC uses a common gut bacterium called Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron to worsen EHEC infection. B. thetaiotaomicron is a predominant species in the gut’s microbiota, which consists of tens of trillions of microorganisms used to digest food, produce vitamins, and provide a barrier against harmful microorganisms.

“EHEC has learned to how to steal scarce resources that are made by other species in the microbiota for its own survival in the gut,” said lead author Dr. Meredith Curtis, Postdoctoral Researcher at UT Southwestern.

The research team found that B. thetaiotaomicron causes changes in the environment that promote EHEC infection, in part by enhancing EHEC colonization, according to the paper, appearing in the journal Cell Host Microbe.

“We usually think of our microbiota as a resistance barrier for pathogen colonization, but some crafty pathogens have learned how to capitalize on this role,” said Dr. Vanessa Sperandio, Professor of Microbiology and Biochemistry at UT Southwestern and senior author (left).

“We usually think of our microbiota as a resistance barrier for pathogen colonization, but some crafty pathogens have learned how to capitalize on this role,” said Dr. Vanessa Sperandio, Professor of Microbiology and Biochemistry at UT Southwestern and senior author (left).

EHEC senses changes in sugar concentrations brought about by B. thetaiotaomicron and uses this information to turn on virulence genes that help the infection colonize the gut, thwart recognition and killing by the host immune system, and obtain enough nutrients to survive. The group observed a similar pattern when mice were infected with their equivalent of EHEC, the gut bacterium Citrobacter rodentium. Mice whose gut microbiota consisted solely of B. thetaiotaomicron were more susceptible to infection than those that had no gut microbiota. Once again, the research group saw that B. thetaiotaomicron caused changes in the environment that promoted C. rodentium infection.

“This study opens up the door to understand how different microbiota composition among hosts may impact the course and outcome of an infection,” said Dr. Sperandio, whose lab studies how bacteria recognize the host and how this recognition might be exploited to interfere with bacterial infections. “We are testing the idea that differential gastrointestinal microbiota compositions play an important role in determining why, in an EHEC outbreak, some people only have mild diarrhea, others have bloody diarrhea and some progress to hemolytic uremic syndrome, even though all are infected with the same strain of the pathogen.”

Other UT Southwestern researchers involved in the work include Dr. Ralph DeBerardinis, Associate Professor with the Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern, Eugene McDermott Center for Human Growth and Development, and Pediatrics, who holds the Joel B. Steinberg, M.D. Chair in Pediatrics and is Sowell Family Scholar in Medical Research; Dr. Zeping Hu, Assistant Professor with Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern and Pediatrics; and Claire Klimko, Research Technician. The work was carried out in collaboration with researchers at Kansas State University and supported by the National Institute of Health and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

epidemic for the first time."

epidemic for the first time.".jpeg) died of the disease.

died of the disease.

.jpg) Åkerlind of the infectious disease unit of Östergötland County told

Åkerlind of the infectious disease unit of Östergötland County told

sprouts from a Dutch grower.

sprouts from a Dutch grower.

.jpg) while a further 50 people were ill with mild symptoms of EHEC.

while a further 50 people were ill with mild symptoms of EHEC.