Food fraud has been going on as long as food has been traded.

Madeleine Ferrières a professor of social history at the University of Avignon, France, wrote in Sacred Cow, Mad Cow: A History of Food Fears, first published in French in 2002, but translated into English in 2006 that, “All human beings before us questioned the contents of their plates. … And we are often too blinded by this amnesia to view our present food situation clearly. This amnesia is very convenient. It allows us to reinvent the past and construct a complaisant, retrospective mythology.”

Madeleine Ferrières a professor of social history at the University of Avignon, France, wrote in Sacred Cow, Mad Cow: A History of Food Fears, first published in French in 2002, but translated into English in 2006 that, “All human beings before us questioned the contents of their plates. … And we are often too blinded by this amnesia to view our present food situation clearly. This amnesia is very convenient. It allows us to reinvent the past and construct a complaisant, retrospective mythology.”

Ferrières provides extensive documentation of the rules, regulations and penalties that emerged in the Mediterranean between the 12th and 16th centuries.

From the review by Professor Chris Elliott of Queen’s University in Belfast, which was published today:

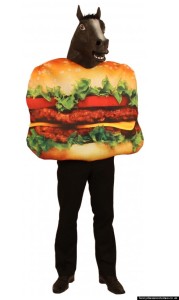

• This review was prompted by growing concerns about the systems used to deter, identify and prosecute food adulteration. The horse meat crisis of 2013 was a trigger, as were concerns about the increasing potential for food fraud and ‘food crime’. Food fraud becomes food crime when it no longer involves random acts by ‘rogues’ within the food industry but becomes an organised activity by groups which knowingly set out to deceive, and or injure, those purchasing food. These incidents can have a huge negative impact both on consumer confidence, and on the reputation and finances of food businesses.

• The review has taken a systems approach based on eight pillars of food integrity, and this report deals with each in turn, making clear that no one element can stand alone. The result is a robust system that puts the needs of consumers before all others; adopts a zero tolerance approach to food crime; invests in intelligence gathering and sharing; supports resilient laboratory services that use standardised, validated methodologies; improves the efficiency and quality of audits and more actively investigates and tackles food crime; acknowledges the key rolegGovernment has to play in supporting industry; and reinforces the need for strong leadership and effective crisis management.

• Consumers First: Government should ensure that the needs of consumers in relation to food safety and food crime prevention are the top priority. The Government should work with industry and regulators to:

• Consumers First: Government should ensure that the needs of consumers in relation to food safety and food crime prevention are the top priority. The Government should work with industry and regulators to:

• _Maintain consumer confidence in food;

• _Prevent contamination, adulteration and false claims about food;

• _Make food crime as difficult as possible to commit;

• _Make consumers aware of food crime, food fraud and its implications; and

• _Urgently implement an annual targeted testing programme based on horizon scanning and intelligence, data collection and well-structured surveys.

Recommendation 2 – Zero Tolerance: Where food fraud or food crime is concerned, even minor dishonesty must be discouraged and the response to major dishonesty deliberately punitive. The Government should:

• _Encourage the food industry to ask searching questions about whether certain deals are too good to be true;

• _Work with industry to ensure that opportunities for food fraud, food crime, and active mitigation are included in company risk registers;

• _Support the development of whistleblowing and reporting of food crime;

• _Urge industry to adopt incentive mechanisms that reward responsible procurement practice;

• _Encourage industry to conduct sampling, testing and supervision of food supplies at all stages of the food supply chain;

• _Provide guidance on public sector procurement contracts regarding validation and assurance of food supply chains; and

• _Encourage the provision of education and advice for regulators and industry on the prevention and identification of food crime.

Recommendation 3 – Intelligence Gathering: There needs to be a shared focus by Government and industry on intelligence gathering and sharing. The Government should:

• _Work with the Food Standards Agency (to lead for the Government) and regulators to collect, analyse and distribute information and intelligence; and

• _Work with the industry to help it establish its own ‘safe haven’ to collect, collate, analyse and disseminate information and intelligence.

Recommendation 4 – Laboratory Services: Those involved with audit, inspection and enforcement must have access to resilient, sustainable laboratory services that use standardised, validated approaches. The Government should:

Recommendation 4 – Laboratory Services: Those involved with audit, inspection and enforcement must have access to resilient, sustainable laboratory services that use standardised, validated approaches. The Government should:

• _Facilitate work to standardise the approaches used by the laboratory community testing for food authenticity;

• _Work with interested parties to develop ‘Centres of Excellence’, creating a framework for standardising authenticity testing;

• _Facilitate the development of guidance on surveillance programmes to inform national sampling programmes;

• _Foster partnership working across those public sector organisations currently undertaking food surveillance and testing including regular comparison and rationalisation of food surveillance;

• _Work in partnership with Public Health England and local authorities with their own laboratories to consider appropriate options for an integrated shared scientific service around food standards; and

• _Ensure this project is subject to appropriate public scrutiny.

Recommendation 5 – Audit: The value of audit and assurance regimes must be recognised in identifying the risk of food crime in supply chains. The Government should:

• _Support industry development of a modular approach to auditing with specific retailer modules underpinned by a core food safety and integrity audit to agreed standards and criteria;

• _Support the work of standards owners in developing additional audit modules for food fraud prevention and detection incorporating forensic accountancy and mass balance checks;

• _Encourage industry to reduce burdens on businesses by carrying out fewer, but more effective audits and by replacing announced audits with more comprehensive unannounced audits;

• _Encourage third party accreditation bodies undertaking food sampling to incorporate surveillance sampling in unannounced audits to a sampling regime set by the standard holder;

• _Work with industry and regulators to develop specialist training and advice about critical control points for detecting food fraud or dishonest labelling;

• _Encourage industry to recognise the extent of risks of food fraud taking place in storage facilities and during transport

• _Support development of new accreditation standards for traders and brokers that include awareness of food fraud; and

• _Work with industry and regulators to introduce anti-fraud auditing measures.

Recommendation 6 – Government Support: Government support for the integrity and assurance of food supply networks should be kept specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and timely (SMART). The Government should:

• _Support the Food Standards Agency’s strategic and co-ordinated approach to food law enforcement delivery, guidance and training of local authority enforcement officers;

• _Support the Food Standards Agency to develop a model for co-ordination of high profile investigations and enforcement and facilitate arrangements to deal effectively with food crime;

• _Ensure that research into authenticity testing, associated policy development and operational activities relating to food crime becomes more cohesive and that these responsibilities are clearly identified, communicated and widely understood by all stakeholders;

• _Ensure that oversight of the ‘Authenticity Assurance Network’ becomes a role for the National Food Safety and Food Crime Committee’;

• _Re-affirm its commitment to an independent Food Standards Agency; and

• _Engage regularly with the Food Standards Agency at a senior level through the creation of a National Food Safety and Food Crime Committee.

Recommendation 7 – Leadership: There is a need for clear leadership and co-ordination of effective investigations and prosecutions relating to food fraud and food crime; the public interest must be recognised by active enforcement and significant penalties for serious food crimes. The Government should:

• _Ensure that food crime is included in the work of the Government Agency Intelligence Network and involves the Food Standards Agency as the lead agency for food crime investigation;

• _Support the creation of a new Food Crime Unit hosted by the Food Standards Agency operating under carefully defined terms of reference, and reporting to a governance board;

• _Support the Food Standards Agency in taking the lead role on national incidents, reviewing where existing legislative mechanisms exist, while arrangements are being made to create the Food Crime Unit; and

• _Require that the Government lead on Operation Opson passes from the Intellectual Property Office to the Food Standards Agency.

Recommendation 8 – Crisis Management: Mechanisms must be in place to deal effectively with any serious food safety and/or food crime incident. The Government should:

• _Ensure that all incidents are regarded as a risk to public health until there is evidence to the contrary;

• _Urge the Food Standards Agency to discuss with the Cabinet Office in their role as co-ordinating body for COBR (Cabinet Office Briefing Room) the planning and organisation of responses to incidents;

• _Urge the Food Standards Agency to implement Professor Troop’s recommendations to put in place contingency plans at the earliest opportunity; and

• _Work closely with the Food Standards Agency to ensure clarity of roles and responsibilities before another food safety and/or food crime incident occurs.

Carried out by officials from the Food Standards Agency (FSA) under the oversight of an independent steering group, the findings are to be considered by the FSA Board at its next meeting on Wednesday 23 November.

Carried out by officials from the Food Standards Agency (FSA) under the oversight of an independent steering group, the findings are to be considered by the FSA Board at its next meeting on Wednesday 23 November.