Many thanks (and no need to apologize for your mom saying Campylobacter the way she does).

Tag Archives: michigan

TB in deer hunters

For a country that still proclaims, we “enjoy the safest food supply in the world” in U.S. Department of Agriculture missives, when we’ve been arguing reduced risk is a better message for 25 years and that there are so many countries with the self-proclaimed title of safest food in the world they can’t all be right – it’s alarming that Mycobacterium bovis has been transmitted from deer to a human.

Deer hunting season in Ontario (that’s in Canada) begins about today.

I never had any interest.

Not a Bambi thing, just thought it was boring.

My dad went a few times but I’m not sure if he enjoyed it or not.

Whatever.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control reports that in May 2017, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services was notified of a case of pulmonary tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis in a man aged 77 years. The patient had rheumatoid arthritis and was taking 5 mg prednisone daily; he had no history of travel to countries with endemic tuberculosis, no known exposure to persons with tuberculosis, and no history of consumption of unpasteurized milk. He resided in the northeastern Lower Peninsula of Michigan, which has a low incidence of human tuberculosis but does have an enzootic focus of M. bovis in free-ranging deer (Odocoileus virginianus). The area includes a four-county region where the majority of M. bovis–positive deer in Michigan have been found.

Statewide surveillance for M. bovis via hunter-harvested deer head submission has been ongoing since 1995; in 2017, 1.4% of deer tested from this four-county region were culture-positive for M. bovis, compared with 0.05% of deer tested elsewhere in Michigan. The patient had regularly hunted and field-dressed deer in the area during the past 20 years. Two earlier hunting-related human infections with M. bovis were reported in Michigan in 2002 and 2004. In each case, the patients had signs and symptoms of active disease and required medical treatment.

Whole-genome sequencing of the patient’s respiratory isolate was performed at the National Veterinary Services Laboratories in Ames, Iowa. The isolate was compared against an extensive M. bovis library, including approximately 900 wildlife and cattle isolates obtained since 1993 and human isolates from the state health department. This 2017 isolate had accumulated one single nucleotide polymorphism compared with a 2007 deer isolate, suggesting that the patient was exposed to a circulating strain of M. bovis at some point through his hunting activities and had reactivation of infection as pulmonary disease in 2017.

Whole-genome sequencing also was performed on archived specimens from two hunting-related human M. bovis infections diagnosed in 2002 (pulmonary) and 2004 (cutaneous) that were epidemiologically and genotypically linked to deer (3). The 2002 human isolate had accumulated one single nucleotide polymorphism since sharing an ancestral genotype isolated from several deer in Alpena County, Michigan, as early as 1997; the 2004 human isolate shared an identical genotype with a grossly lesioned deer harvested by the patient in Alcona County, Michigan, confirming that his infection resulted from a finger injury sustained during field-dressing. The 2002 and 2017 cases of pulmonary disease might have occurred following those patients’ inhalation of aerosols during removal of diseased viscera while field-dressing deer carcasses.

Whole-genome sequencing also was performed on archived specimens from two hunting-related human M. bovis infections diagnosed in 2002 (pulmonary) and 2004 (cutaneous) that were epidemiologically and genotypically linked to deer (3). The 2002 human isolate had accumulated one single nucleotide polymorphism since sharing an ancestral genotype isolated from several deer in Alpena County, Michigan, as early as 1997; the 2004 human isolate shared an identical genotype with a grossly lesioned deer harvested by the patient in Alcona County, Michigan, confirming that his infection resulted from a finger injury sustained during field-dressing. The 2002 and 2017 cases of pulmonary disease might have occurred following those patients’ inhalation of aerosols during removal of diseased viscera while field-dressing deer carcasses.

In Michigan, deer serve as maintenance and reservoir hosts for M. bovis, and transmission to other species has been documented. Since 1998, 73 infected cattle herds have been identified in Michigan, resulting in increased testing and restricted movement of cattle outside the four-county zone. Transmission to humans also occurs, as demonstrated by the three cases described in this report; however, the risk for transmission is understudied.

Similar to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, exposure to M. bovis can lead to latent or active infection, with risk for eventual reactivation of latent disease, especially in immunocompromised hosts. To prevent exposure to M. bovis and other diseases, hunters are encouraged to use personal protective equipment while field-dressing deer. In addition, hunters in Michigan who submit deer heads that test positive for M. bovis might be at higher risk for infection, and targeted screening for tuberculosis could be performed. Close collaboration between human and animal health sectors is essential for containing this zoonotic infection.

Notes from the Field: Zoonotic mycobacterium bovis disease in deer hunters—Michigan, 2002-2017

James Sunstrum, MD1; Adenike S hoyinka, MD2; Laura E. Power, MD2,3; Daniel Maxwell, DO4; Mary Grace Stobierski, DVM5; Kim Signs, DVM5; Jennifer L. Sidge, DVM, PhD5; Daniel J. O’Brien, DVM, PhD6; Suelee Robbe-Austerman, DVM, PhD7; Peter Davidson, PhD5

Campy in puppies: Petland store faces 3rd lawsuit this year alleging it knowingly sold sick puppies

A Petland store in Michigan is facing its third lawsuit this year after a man said he was hospitalized after buying a puppy later found to be sick from the store.

Doug Rose said he became infected with Campylobacter — a multi-drug resistant infection — after he and his wife Dawn purchased Thor, a beagle-pug mix puppy that the couple said was infected with parasites, suffered from coccidia and giardia, and had an upper respiratory infection, The Oakland Press reported.

Doug Rose said he became infected with Campylobacter — a multi-drug resistant infection — after he and his wife Dawn purchased Thor, a beagle-pug mix puppy that the couple said was infected with parasites, suffered from coccidia and giardia, and had an upper respiratory infection, The Oakland Press reported.

The couple said the same veterinary clinic that gave the dog a clean bill of health through the Petland in Novi also diagnosed the puppy with a number of ailments.

Symptoms of Campylobacter infections can include abdominal pain, diarrhea, headache, fever, nausea and vomiting.

The couple is seeking monetary compensation after Doug Rose said he required multiple weeks of medical treatment.

Randy Horowitz, who owns the Petland in the Detroit suburb, told the newspaper the case would be resolved to “reflect the facts.”

A lawsuit filed by 17 plaintiffs against Horowitz was dismissed earlier this year. The lawsuit alleged that Horowitz knowingly sold puppies suffered from genetic defects.

A lawsuit was filed in April by nine families alleging that puppies they purchased suffered from a number of medical issues.

Other pet owners have claimed puppies they purchased from that Petland location became sick.

In January, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released results of a multi-state investigation that showed 113 cases of Campylobacter across 17 states linked to pet stores. A majority of people reported becoming sick after coming in contact with a puppy purchased from a Petland store or after coming in contact with another human who had recently purchased a dog from a Petland store.

Michigan’s hepatitis A problem is a public health cycle

Next month I’ll be in Michigan talking food safety with Don at a live podcast recording as part of the Global Food Law Current Issues Conference.

Added to the list for our chat is a local issue, a massive hepatitis A outbreak. Tragically, according to USA Today, the outbreak has been linked to 27 deaths and hundreds of cases.

Wrapped up in this outbreak is the intersection of intravenous drug use; individuals in the homeless population; and, folks working in food service. Public health is complicated.

Most of those who have died in Michigan in this outbreak are 50 or older, Fielder said. And they died of liver failure, septic shock or other organ failure.

“Generally, it’s been people who are more sick or people who have less access to health care,” Fielder said. “You know, we’ve also seen a homeless component to this. We’re seeing this driven by a substance use disorder risk group.”

People who use illegal drugs account for about half of outbreak-related cases..

“It’s a very hard group to reach, and it’s a very hard group to get public health messaging to. There’s a lot of trust issues with government entities in general. So there’s a lot of outreach going out from local public health to … people they do trust in the community.”

As of Wednesday before Memorial Day, the hardest hit areas are Macomb County, north of Detroit, with 220 cases; Detroit itself with 170; elsewhere in Wayne County, where Detroit is located, with 144; and Oakland County, to the west of Macomb County where Pontiac is located, with 114 cases, according to the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services.

Part of the problem: As many as 35 restaurant workers in the Detroit area were found to have the virus and may have spread it unknowingly to diners. The virus is contagious weeks before a person begins to exhibit symptoms, which makes it extremely challenging for public health officials to manage.

Chlorine works: 12 dead, 87 sick from Legionnaires’ linked to Michigan water supply 2014-15

An outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease that killed 12 people and sickened at least 87 in Flint, Mich., in 2014 and 2015 was caused by low chlorine levels in the municipal water system, scientists have confirmed. It’s the most detailed evidence yet linking the bacterial disease to the city’s broader water crisis.

Rebecca Hersher of NPR reports that in April 2014, Flint’s water source switched from Lake Huron to the Flint River. Almost immediately, residents noticed tap water was discolored and acrid-smelling. By 2015, scientists uncovered that the water was contaminated with lead and other heavy metals.

Rebecca Hersher of NPR reports that in April 2014, Flint’s water source switched from Lake Huron to the Flint River. Almost immediately, residents noticed tap water was discolored and acrid-smelling. By 2015, scientists uncovered that the water was contaminated with lead and other heavy metals.

Just months after the water source changed, hospitals were reporting large numbers of people with Legionnaires’ disease.

“It’s a pneumonia, but what’s different about it is, we don’t share it like we do the flu or common cold,” explains Michele Swanson of the University of Michigan, who has been studying Legionnaires’ for 25 years. “It’s caused by a bacterium,Legionella pneumophila, that grows in water.”

The bug can enter the lungs through tiny droplets, like ones dispersed by an outdoor fountain or sprinkler system, or accidentally inhaled if a person chokes while drinking.

“If you don’t have a robust immune system, the microbe can cause a lethal pneumonia,” she says. In a normal year, the disease is relatively rare — about six to 12 cases per year in the Flint area, according to Swanson. During the water crisis, that jumped up to about 45 cases per year.

Although the outbreak of Legionnaires’ happened at the same time as the Flint water crisis, it was initially unclear how the two were connected. After earlier research suggested that chlorine levels might be the key, Swanson and colleagues at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Sammy Zahran of Colorado State University and a team of researchers at Wayne State University in Detroit, began analyzing detailed water and epidemiological data from the six-year period before, during and after the crisis.

“We know that Legionella is sensitive to chlorine in the laboratory,” says Swanson. The chlorine makes it difficult for the bacteria to replicate, which is one reason water companies often add chlorine to their systems. But when Flint’s water source changed, the chlorine level dropped and cases of Legionnaires’ disease spiked. “It was the change in water source that caused this Legionnaires’ outbreak,” Swanson says.

The new research was published in a pair of studies in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and the journal mBio on Monday. The conclusion may bolster parts of the case being brought against Nick Lyon, the former Michigan Department of Health and Human Services director, who is being tried for involuntary manslaughter in connection with the Legionnaires’ deaths.

From April 2014 to October 2015, the Flint River served as Flint’s water source. During the same period, cases of Legionnaires’ disease increased from less than a dozen per year to about 45 per year, and 12 people died of the waterborne disease.

The new studies also suggest that a complex set of factors may be responsible for low chlorine levels during the crisis. In addition to killing microbes, chlorine can react with heavy metals like lead and iron, and with organic matter from a river. That means lead and iron in the water may have decreased the amount of chlorine available to kill bacteria.

Probably Norovirus: At least 35 sickened at Michigan restaurant

Rachel Greco of the Lansing State Journal reports at least 35 people have reported getting sick after eating at downtown Grand Ledge restaurant The Log Jam in the last two weeks, according to public health officials.

The West Jefferson Street restaurant closed Monday, six days after the first eight illness complaints were reported to the health department on Nov. 22, said Abigail Lynch, a spokesperson for the Barry-Eaton County Health Department.

The West Jefferson Street restaurant closed Monday, six days after the first eight illness complaints were reported to the health department on Nov. 22, said Abigail Lynch, a spokesperson for the Barry-Eaton County Health Department.

Those Log Jam customers reported eating there Nov. 19, she said.

Lynch said callers reported norovirus symptoms, which include diarrhea, nausea, stomach cramps and vomiting. She said health department staff suspect a norovirus outbreak, but are awaiting test results to confirm it.

The Nov. 22 reports did not prompt the restaurant to close or for the health department to issue a public statement about the suspected outbreak, Lynch said, because the health department didn’t believe there was “an ongoing threat to public health.”

Lynch said department staff visited the restaurant Nov. 22, and staff there cleaned the interior of the eatery with bleach, threw out any prepared food and emphasized hand washing practices with employees.

Since Nov. 22 at least 27 additional reports of illness have been made by Log Jam customers to the health department, Lynch said. Most of those people reported eating at the restaurant Nov. 25 and reports were still coming in, she said.

“Based on that, when we left on (Nov. 22) we felt we had put proper interventions in place to prevent further illness,” Lynch said. “This just happened to be one of those instances where it wasn’t.”

Lynch said the restaurant was closed Nov. 27 for another cleaning that was supervised by health department staff, and re-opened the next day. She said all of the restaurant’s prepared foods were thrown out and employees were informed again about the importance of hand washing.

A person who answered the phone at The Log Jam Wednesday morning declined to comment on the suspected outbreak and referred all questions to the health department.

A Nov. 27 post on The Log Jam’s Facebook page reads, “It seems that there has been an outbreak of a viral gastroenteritis in the community. We have consulted with the health department and they confirmed that this very contagious virus has made some people very ill in our town…Since our water heater went up in flames, and we had to close for repairs, we took full advantage of our down time to disinfect every square inch of our facility.”

‘I’m kind of tired after 28 years, here’s my resignation’ Michigan food supervisor forced to resign

I get it.

Burdened with never-ending bureaucracy, who wouldn’t resign.

I did (KState said I resigned, but really, they fired my ass).

I did (KState said I resigned, but really, they fired my ass).

And followed a girl to Brisbane.

But the only thing wrong about my resignation was I never got any severance from Kansas State University, and still cringe every time I hear about the parachutes — golden or not — bureaucrats get upon departure.

I was dumb about that.

I was also hopelessly naive about my belief that universities were places of higher learning and that effort and achievement would be honored.

Nope

Cody Combs of WWMT reports a former employee of a West Michigan county health department once in charge of overseeing restaurant inspections is now coming under criticism after the I-Team learned the employee was forced to resign.

This comes as the Newschannel 3 I-Team uncovers how some say the restaurant inspector neglected to keep up with inspections, potentially putting the safety of many in and around West Michigan at risk.

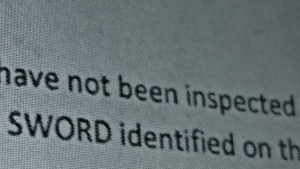

The I-Team started asking questions about the health inspections after portions of a Van Buren/Cass District Health Department document were anonymously sent to Newschannel 3.

“Inspect the 40 restaurants which have not been inspected since 2015,” reads the document.

That rate of inspections falls far below state regulations, according to staffers at several West Michigan county health departments.

The I-Team then pored over Van Buren/Cass Health Department meeting minutes, and found a brief mention during a meeting in March of a resignation from a worker named Cary Hindley, now the former food service supervisor.

Over at the Van Buren/Cass Health Department, we asked Director Jeff Elliott about the inspections or lack thereof, and Elliott explained Hindley’s departure.

“He said, you know what Jeff, all the regulations we have to follow and everything, he said, I’m kind of tired after 28 years, here’s my resignation,” Elliott said.

But Elliott disagreed with the internal document saying 40 restaurants were last inspected in 2015.

But Elliott disagreed with the internal document saying 40 restaurants were last inspected in 2015.

“I don’t think that’s gospel,” he said.

Elliott says the files may need to be located.

Other staffers, speaking on the condition of anonymity, say finding the documents, if they exist, may prove impossible.

At Wednesday’s Board of Health meeting, more concerns about the restaurant inspection discrepancies were voiced from board members, as well as other county health officials.

It was raw egg based Hollandaise sauce: Marquette County in Michigan frontrunner for 2017 least informative press release

Raw egg-based dished – the purvey of every food porn chef – are not just a problem in Australia.

Marquette County in Michigan has recently experienced a small Salmonella outbreak among residents.

But that’s all that is being reported.

Coral Beach of Food Safety News called Patrick L. Jacuzzo, Marquette County director of environmental health, who described the outbreak as “restaurant associated” and said the assumption as of Friday afternoon was that raw, unpasteurized eggs served in Hollandaise sauce with eggs Benedict were the source.

So far, 8 people had been sickened.

A table of raw egg-based outbreaks in Australia is available at:

https://barfblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/raw-egg-related-outbreaks-australia-5-1-17.xlsx

Effective inspections: Be kind and considerate

Conducting food safety inspections requires interpersonal skills and technical expertise. This requirement is particularly important for agencies that adopt a compliance assistance approach by encouraging inspectors to assist industry in finding solutions to violations.

This article describes a study of inspections that were conducted by inspectors from the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development Food and Dairy Division at small-scale processing facilities. Interactions between inspectors and small processors were explored through a qualitative, ethnographic approach using interviews and field observations. Inspectors emphasized the importance of interpersonal skills such as communication, patience, empathy, respect, and consideration in conducting inspections.

This article describes a study of inspections that were conducted by inspectors from the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development Food and Dairy Division at small-scale processing facilities. Interactions between inspectors and small processors were explored through a qualitative, ethnographic approach using interviews and field observations. Inspectors emphasized the importance of interpersonal skills such as communication, patience, empathy, respect, and consideration in conducting inspections.

This article examines how these skills were applied, how inspectors felt they improved compliance, the experiences through which inspectors attained these skills, and the training for which they expressed a need. These results provide new insights into the core competencies required in conducting inspections, and they provide the groundwork for further research.

Interpersonal skills in the practice of food safety inspections: A study of compliance assistance

Journal of Environmental Health , December 2016, Volume 79, No. 5, 8–12

Jenifer Buckley, PhD

Shigellosis outbreak in Flint, Mich. because people afraid to wash hands

Don’t eat poop (and if you do, make sure it’s cooked).

These are the basics of public health.

These are the basics of public health.

Most of us are taught from a very early age that hand-washing is an easy, essential way of keeping ourselves clean and healthy. But residents of Flint, Michigan and surrounding areas have been forgoing this common practice out of fear of the water’s toxicity. Genesee county, of which Flint is a the largest city, and the adjacent county of Saginaw combined have experienced an outbreak of 131 cases of Shigellosis (named after the bacteria that causes it, Shigella). It’s a bloody diarrheal disease transmitted via tiny amounts of contaminated fecal matter. It typically lasts about a week, but can also cause patients to feel like they have to go to the bathroom even when they have no more waste in their systems. Additionally, the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) also notes that “may be several months before [patients] bowel habits are entirely normal.”

In 2013, there were just under five cases reported per every 100,000 people in America. The outbreak in Michigan far exceeds that number, and it’s likely because residents in the area are afraid to use their tap water, which was found to have toxic levels of lead, a heavy metal that can cause neurological problems when it builds up in the body, in 2015. Even though the water was deemed safe for consumption with a proper filter, people in the area are still scared to wash their hands at all, according to the Washington Post.

Instead, they’re cleaning themselves using baby wipes—aren’t nearly as effective as disinfectant as good old-fashioned scrubbing—which should take about 20 seconds to ensure that any potential pathogens are washed down the drain.

“Some people have mentioned that they’re not going to expose their children to the water again,” Jim Henry, Genesee County’s environmental health supervisor, told CNN.