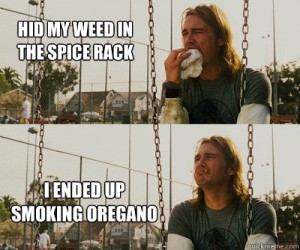

Before marijuana could be bought at a dispensary – Australia, you’re so behind the times on this, same-sex marriage and asylum seekers – would-be middle-school dealers would often pass off bags of oregano as weed.

Those who smoked it got a headache: they did not get high.

Those who smoked it got a headache: they did not get high.

A couple of Australian supermarkets were caught doing a similar bait and switch.

Food fraud.

Esther Han of the Canberra Times reports Aldi and supermarket supplier Menora have admitted to selling nearly 190,000 units of adulterated oregano products over a one-year period and have promised never – never ever double secret probation promise — to do it again.

The budget grocery chain and Menora have signed court enforceable undertakings with the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, committing to conduct annual testing of the composition of their herb and spice products.

Aldi sold more than 126,800 units of its Stonemill oregano across its 400 stores in 2015, documents show. And 61,480 Menora-branded products were sold at Coles, Woolworths, IGA and other stores in NSW, Vic, WA and SA in the same year.

They claimed the products were 100 per cent dried oregano leaves, despite a “substantial presence of olive leaves”.

“This is extremely bad behaviour. I don’t think it’s in anybody’s head that you’re getting anything other than pure oregano and our message to retailers is: ‘Check the products you’re selling,” said ACCC chairman Rod Sims.

“The offer of refunds is there. If you take back the empty container you’ll get a refund, take back proof of purchase, you’ll get a refund.”

The undertakings follow an investigation by consumer group Choice, which in April said laboratory tests showed seven out of 12 popular oregano products were less than 50 per cent oregano leaves. They were instead bulked out with olive and sumac leaves.

The worst offender was Master of Spices, which was only 10 per cent oregano, followed by Hoyt’s, at 11 per cent, and Aldi’s Stonemill, at 26 per cent.

The test results showed Spice & Co and Menora’s products were only a third oregano, Spencers was 40 per cent and G Fresh was 50 per cent.

Choice spokesman Tom Godfrey said as dried oregano was a fixture in most kitchens across the country, the undertakings were a real win for Australian consumers.

“We need be able to trust what is written on the labels of the foods we purchase in our supermarkets,” he said.