I didn’t blog for the last two months. I haven’t done that in 16 years. I haven’t done that ever. Throw in the news and I haven’t done it, ever, in 28 years.

Only once have I ever stopped daily writing over that time period – one week in 2004.

But, I keep falling and my head hurts, so I’m easing back in because it keeps my brain active.

But, I keep falling and my head hurts, so I’m easing back in because it keeps my brain active.

I haven’t had a pay cheque in four years. There’s lots of work at home jobs out there now, which is ironic because I got fired by Kansas State for working at home.

Anyone got work for me?

I’m wonderin’ how this will go.

Got lotsa support from Amy and Sorenne and the rest of the fam.

Jim Robbins of the New York Times reports on the wonderin’ of researchers who ask, Are the wolves of Yellowstone National Park the first line of defense against a terrible disease that preys on herds of wildlife?

That’s the question for a research project underway in the park, and preliminary results suggest that the answer is yes. Researchers are studying what is known as the predator cleansing effect, which occurs when a predator sustains the health of a prey population by killing the sickest animals. If the idea holds, it could mean that wolves have a role to play in limiting the spread of chronic wasting disease, which is infecting deer and similar animals across the country and around the world. Experts fear that it could one day jump to humans.

“There is no management tool that is effective” for controlling the disease, said Ellen Brandell, a doctoral student in wildlife ecology at Penn State University who is leading the project in collaboration with the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Park Service. “There is no vaccine. Can predators potentially be the solution?”

Many biologists and conservationists say that more research would strengthen the case that reintroducing more wolves in certain parts of the United States could help manage wildlife diseases, although the idea is sure to face pushback from hunters, ranchers and others concerned about competition from wolves.

Chronic wasting disease, a contagious neurological disease, is so unusual that some experts call it a “disease from outer space.” First discovered among wild deer in 1981, it leads to deterioration of brain tissue in cervids, mostly deer but also elk, moose and caribou, with symptoms such as listlessness, drooling, staggering, emaciation and death.

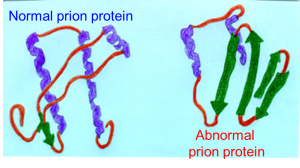

It is caused by an abnormal version of a cell protein called a prion, which functions very differently than bacteria or viruses. The disease has spread across wild cervid populations and is now found in 26 states and several Canadian provinces, as well as South Korea and Scandinavia.

The disease is part of a group called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, the most famous of which is bovine spongiform encephalopathy, also known as mad cow disease. Mad cow in humans causes a variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and there was an outbreak among people in the 1990s in Britain from eating tainted meat.

Cooking does not kill the prions, and experts fear that chronic wasting disease could spread to humans who hunt and consume deer or other animals that are infected with it.

The disease has infected many deer herds in Wyoming, and it spread to Montana in 2017. Both states are adjacent to Yellowstone, so experts are concerned that the deadly disease could soon makes its way into the park’s vast herds of elk and deer.

The disease has infected many deer herds in Wyoming, and it spread to Montana in 2017. Both states are adjacent to Yellowstone, so experts are concerned that the deadly disease could soon makes its way into the park’s vast herds of elk and deer.

Unless, perhaps, the park’s 10 packs of wolves, which altogether contain about 100 individuals, preyed on and consumed diseased animals that were easier to pick off because of their illness (The disease does not appear to infect wolves).

“Wolves have really been touted as the best type of animal to remove infected deer, because they are cursorial — they chase their prey and they look for the weak ones,” said Ms. Brandell. By this logic, diseased deer and other animals would be the most likely to be eliminated by wolves.

Preliminary results in Yellowstone have shown that wolves can delay outbreaks of chronic wasting disease in their prey species and can decrease outbreak size, Ms. Brandell said. There is little published research on “predator cleansing,” and this study aims to add support for the use of predators to manage disease.

We’re all wonderin’.

On Friday, researchers with the

On Friday, researchers with the