Ashley Chaifetz, a PhD student studying public policy at UNC-Chapel Hill, writes:

Winter storm Pax pelted North Carolina with an initial dose of snow and freezing rain, and is now traveling north on I-95. Although I’ve been fortunate so far, power outages are already affecting hundreds of thousands of Southerners. Losing electricity can be a nightmare — especially if it is for more than a couple of hours.

Alongside 4,500 of our neighbors, we spent four nights in a row without power in DC in the summer of 2013. It was hot and humid, with temperatures in the 90s F not C). Our attempts to cook without electricity in the dark felt very much like a modern version of Little House on the Prairie. All I could think was that, if this was hurricane or a snowstorm, we would have had time to prepare (but maybe not).

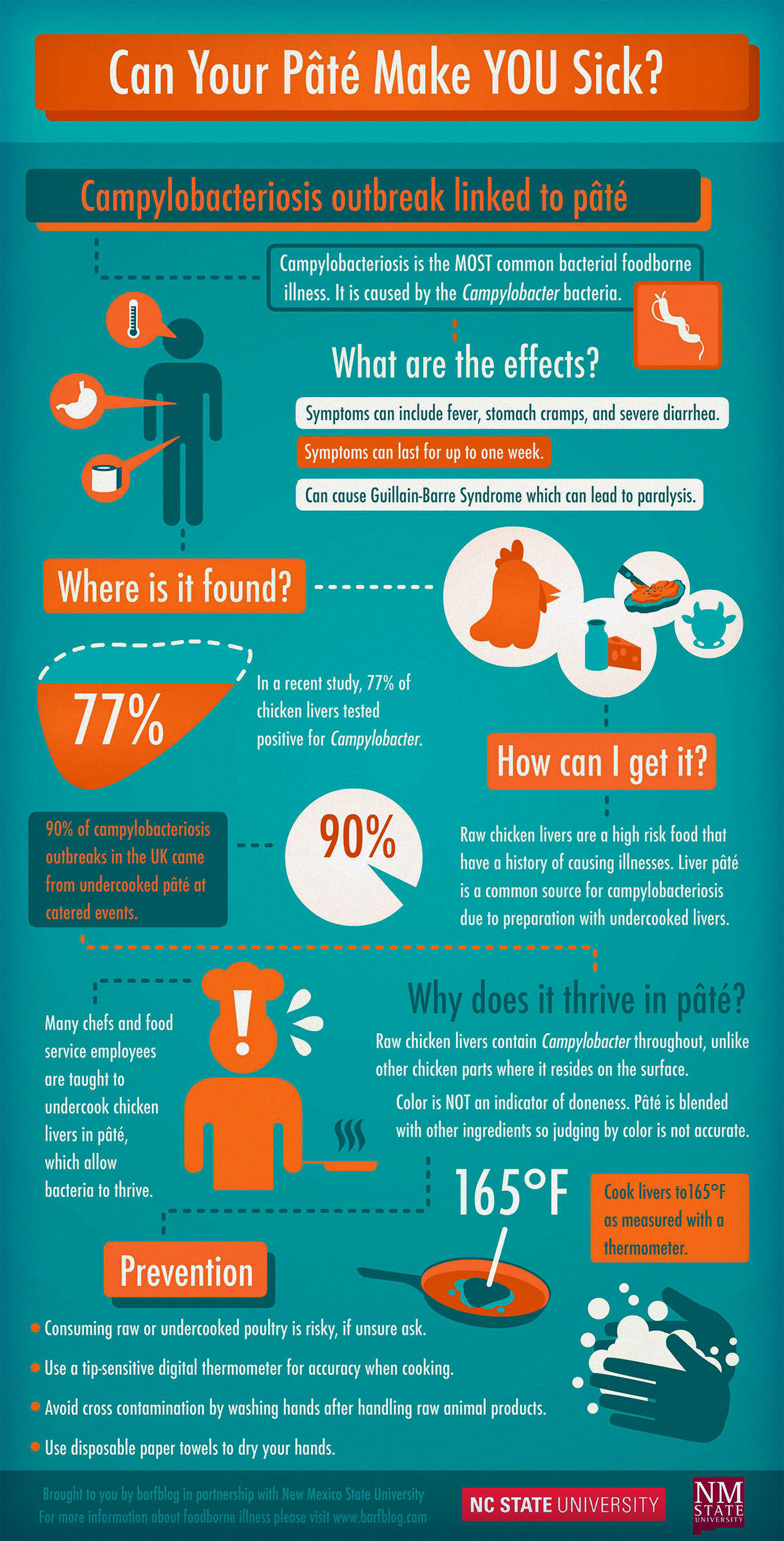

There are currently 800,000 people without power from the snowstorm, leaving many with a food safety situation — a refrigerator with most of last week’s vegetables, defrosting chicken, jars of jams, peanut butter, and tomato sauce, cartons of eggs, chunks of cheese, quarts of milk, and once-canned goods stored in Tupperware. I know I would not be ready to toss all those vegetables into the compost, but depending on the time and temperature, some fridge contents will have to go.

According to USDA FSIS’s estimates, a closed fridge will keep its contents at refrigeration temperatures for about four hours and a closed freezer will keep food close to freezing for about 48 hours after the power goes out. If food temperatures rise above 41°F for more than four hours, pathogens within any meat, seafood, poultry, and dairy products (as well as many cooked foods) can grow to problematic levels. There is an increased risk in  temperature-abused leftovers made with high-protein foods (meat and meat substitutes); soft cheeses; milk and cream-based products; sliced tomatoes and cut leafy greens; and cooked pasta or rice. In the freezer, if meat, poultry, seafood or dairy products still have ice crystals, you can refreeze them when the power returns. If they are thawed for more than a couple of hours, they can be risky.

temperature-abused leftovers made with high-protein foods (meat and meat substitutes); soft cheeses; milk and cream-based products; sliced tomatoes and cut leafy greens; and cooked pasta or rice. In the freezer, if meat, poultry, seafood or dairy products still have ice crystals, you can refreeze them when the power returns. If they are thawed for more than a couple of hours, they can be risky.

Making the risk management decision without a fridge/freezer thermometer and a food thermometer is tough and losing a bunch of food can be an expensive lesson. It isn’t a fantastic idea to guess temperatures without a thermometer, either; a guesstimate can increase risk of illness or lead to more waste.